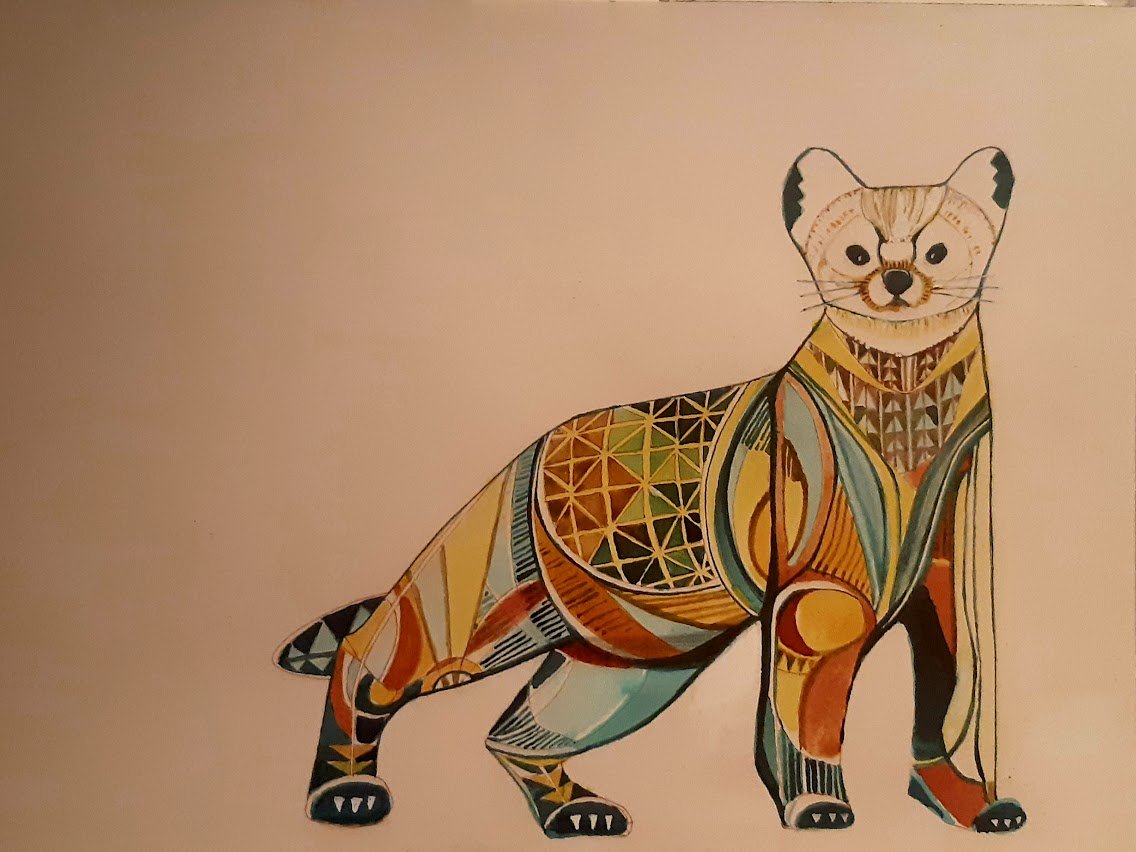

Under the grid patterns of a city there’s a life that breaks through and carries an overgrown existence at the margins. I prefer big cities because they’re more unruly so I chose to live in them: Mexico D.F., Toronto. I’d take long walks or long rides on street cars to watch the avenues and parks unfold, looking for the pockets where something unexpected bloomed under the publicity of billboard adds, under the buzz of engines and electric wires and the clock-work of subway stops. A breakdancer all alone in an empty corner of a public square, a speaker on the floor and through it a loud burst of hip-hop. A middle-aged man sitting on a bench, eyes closed, taking in the sun, for a moment not a person with a job but just a body looking for warmth. A group of drummers in a populated circle and among them a woman resembling a hawk, the sides of her head shaved and her black hair rising and melting down, and she didn´t bang on a drum, she contributed long whistles and sharp shouts. I looked at her and thought that most of us humans are like beavers: we wreck the forests to build our dams, we’re industrious and destructive and disciplined and slightly overweight, but some humans manage to be like birds and they don’t build anything grand; they just fly and hunt for survival. I found comfort in the strangeness of the woman, same as I found comfort in the quick breath of the squirrels pulsing on neighbourhood trees, the pigeons on roofs and ledges, and (once) a real hawk perched just for a moment on a balcony rail.

There was a man at an intersection in Montreal who waited for the streetlights to go red and asked for money with a cat sitting on his shoulder. He spoke to me in French and I couldn’t understand a thing except “miau-miau” which he would say as if speaking on behalf of the cat. I smiled and gave him money and he spoke more French and said “miau-miau” a few more times. The cat was silent and still, relaxed, entertained by the movements of the city from his vantage point. The cat was grey, short-haired and beautiful. The man had short hair, wore a leather jacket and was also beautiful. I have a cat of my own, also grey and short-haired, but he only lets me hold him for a moment. I love cats because they'll fuss in your arms, fight for their independence, demand to be left alone and come to you only if they feel like it (they remain some of the least domesticated of our pets). My cat, in his captivity, needs to constantly reassert his autonomy. This other cat was free to run away but chose the man and remained on his shoulder, helping him make a living in between the traffic.

I lived for a while in a brick building framed by a massive maple tree. The tree stretched across all the edges of my window. I was moved by its size and power when it was just the dark of its bones against the white of the winter, and during the fall when the glory of the yellow and red leaves became overwhelming. I ask myself if aliens looking at us from far away will wonder how there could be such a thing as a maple tree. Some trees are pruned or harvested, kept within reasonable sizes, made productive or ornamental, but the one outside my building grew large and feral, without obstacles, overpowering the nearby houses, feeding on the soil, the sun, the rain and the wind, with no need of us. I loved that tree especially, but I loved all the maple trees looming above me within Canadian cities; giants, all of them, stretching their lives beyond our human boundaries.

The untamed maple tree outside my window, the hawk on the balcony of a condo building, the woman who resembled a hawk and the friendship between the man and the cat at that corner of Montreal, all bloomed out of domestic sidewalks, negotiating a wilderness among us while navigating our paved world, keeping parts of them wild.

There's a war between the forces that bulldoze the ground and regulate our minutes, arrange us in lines of mechanised movements, ensure our productivity and purchasing power, erect cost-efficient buildings and structures making them plain, practical, void of character and decorations on one side, and on the other a relentless beauty finding a way out, regardless, in between the cracks of our streets.

The machines are implacable but nature is a strong survivor, opening its way through the smoke and the tar. Maybe humans will be gone for good one day, our cement and steel ruins will get covered with grass, and grass will win in the end. The machines are killing the mountains but not yet fast enough. We still live under the comfort of trees. The trees breathe out their might and age, their scent and sap and their sleeping birds above us. They remind us we have bones, like the wolves, like the bears, we have eyes and pupils that contract in the light, same as a rabbit, same as a fox. We have warm blood and our bodies tremble with pleasure, quicken with fear. A part of us still belongs to a wilderness and carries the ancient memory of an open sky. A part of us just wants to sing old songs, for that forgotten sky.

Where’s the music that’s entirely ours? It’s in our longing for the time when we didn’t have boundaries between ourselves and nature (because we’re nature and there are no boundaries), it’s also in our unique roots and flavours and questions and ceremonies. I used to live in a tiny studio in a condo for young professionals, near the lake in Toronto. I lived in the gentrified part of an urban geography divided in two by Dufferin Street. On the other side the blocks were noisier, darker in skin colours, thicker in accents and community. There was a varied chorus of sounds there, from people who travelled all the way from a different country or continent to arrive in Toronto, to adapt then to the new language and the new rules while holding on to their own heartaches and nostalgias, their way of spicing food and worshipping God, their way of sitting among family and celebrate a wedding, their way of carrying their hair, their way of singing. On my end, on the other side of Dufferin Street, there seemed to be very little of that; the well-toned, gym-trained people looked like they bought their clothes from the same fashionable stores, holding dogs manicured in the same grooming places, using their spare times to eat at the same trendy restaurants. There’s a war between the forces that want to erase the songs our old communities kept alive to keep themselves living, the forces that prefer our identity to be something sold in stores and prescribed in corporate-sponsored magazines on one side, and on the other the relentless beauty of immigrant, working-class neighbourhoods where the hallways in apartment buildings smell of curry and you can almost hear scotch bonnet peppers sizzling in hot pans, and someone plays the guitar leaning in a doorway, and someone belts the lyrics to the loud music in their living room while the neighbours don’t mind.

The world is relentless. It breaks our hearts. But beauty is also relentless and not dead yet, so there’s hope. If we look and hear closely, within the cogs of the city we can find the pockets where the echoes of a wild music keep humming through the streets.